Deep dive on selected liquidity related considerations

Table of contents / search

Table of contents

Executive summary

Introduction

Macroeconomic environment and market sentiment

Asset side

Liabilities: funding and liquidity

Capital and risk-weighted assets

Profitability

Operational risks and resilience

Deep dive on selected liquidity related considerations

Policy conclusions and suggested measures

Annex: Sample of banks

Abbreviations and acronyms

List of figures

Search

Chapter on Liquidity positions and NSFR covers general trends and developments on the LCR and NSFR. In contrast, the following two sub-chapters provide a more in-depth analysis focussing specifically on LCR-related topics, which have been of particular interest in explaining some of the general trends and developments described above. Chapter on The role of deposits exempted from the calculation of the outflows in the evolution of EU banks’ LCR covers how the LCR trend in recent years has been influenced by the development of customer deposits, which has been driven by the prevailing interest rate environment. Chapter The impact of lower excess reserves on EU banks’ liquidity ratios and liquidity management tries to make a link between general market liquidity and its impact on banks’ LCRs and, in particular, their liquidity buffers. The chapter concludes that the decline in market liquidity requires banks to manage their liquidity buffers more cautiously.

The role of deposits exempted from the calculation of the outflows in the evolution of EU banks’ LCR

Looking back to 2023, although banks reported a decline in their HQLAs (i.e. the numerator of the LCR), this was more than offset by a drop in the LCR net outflows (i.e. the denominator of the LCR) leading to a rise in LCR. The decline in net outflows was to a large extent explained by an increase in deposits that are exempted from the calculation of the outflows, including certain categories of term deposits (Figure 70). It is assumed that the attractiveness of term deposits increased in parallel with higher interest rates, and it was largely responsible for the more than 60% annual increase in exempted deposits reported in 2023. This increase put downward pressure on the outflows from retail deposits (pre-weight), which was the category of outflows that fell by most in 2023, contributing to an annual increase in the LCR by 4 percentage points.

In 2024, the trend in exempted deposits, including term deposits, reversed after the EU central banks widely began to lower their policy interest rates due to decreasing inflationary pressures. This was, accordingly, reflected in the evolution of exempted deposits, which initially stabilised and during the second half of 2024 started to shrink. This contributed to an increase in the outflows from retail deposits that are part of the LCR’s denominator (pre-weight), and to a decrease in the LCR ratio in 2024.

Source: ECB, EBA Supervisory Reporting data

Examining the evolution of exempted term deposits by country, it is observed that for 6 out of 17 countries, these deposits decreased. Meanwhile, the proportion for the remaining countries remained broadly stable. In percentage of total assets, the proportion of deposits exempted from the calculation of the outflows shows significant heterogeneity across Member States. As of December 2024, the shares range from 0.6% in Finland to 16.7% in Estonia of total assets, which also reflect the relevance of deposits in banks’ overall funding mix in several cases (on deposit mix, see Chapter on Funding - state of play).

Source: EBA Supervisory Reporting data

The impact of lower excess reserves on EU banks’ liquidity ratios and liquidity management

Since the aftermath of the GFC, major central banks have actively used liquidity tools to steer financial conditions. These tools were initially introduced to produce credit easing and to safeguard financial stability (e.g. the Federal Reserve’s QE1 and QE2 programmes and the ECB’s three-year long-term refinancing operations (LTRO) programmes), and later on to support central banks’ price stability mandates (e.g. the Federal Reserve’s QE3 and the ECB’s and the Swedish Riksbank's asset purchase programmes). Finally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, large-scale liquidity-providing measures were deployed to protect the financial system in the extraordinary stress situation. After the pandemic crisis, central banks started to gradually shrink their balance sheets by terminating the long-term liquidity operations and/or allowing purchased assets to mature without reinvestments.

From banks’ perspective, central bank reserves are held to satisfy the mandatory minimum reserve requirements (MRRs). Additionally, banks may hold reserves in excess of their MRRs, either as ‘voluntary reserves’ or as ‘involuntary reserves’. ‘Voluntary reserves’ are those that banks choose to hold above the required minimum, often for purposes such as liquidity risk management, regardless of how they were acquired (e.g. through central bank operations). The term refers to the intention to hold reserves, not the method of acquisition. ‘Involuntary reserves’ arise when banks accumulate reserves passively, for example, when they receive payments from the central bank in exchange for assets sold during open market operations. Either way, reserves are the most liquid component of Level 1 HQLA assets for banks. Until today, the abundance of excess reserves has allowed EU banks to report LCR ratios well above the 100% minimum requirement, and many banks may also have felt encouraged to reduce their holdings of other Level 1 and Level 2 HQLA assets given the large amounts of reserves in the system. With the central banks now gradually draining excess reserves, banks have had to start managing their HQLA portfolios more actively to ensure that they can satisfy their minimum liquidity coverage ratios even in a world of permanently lower reserves.

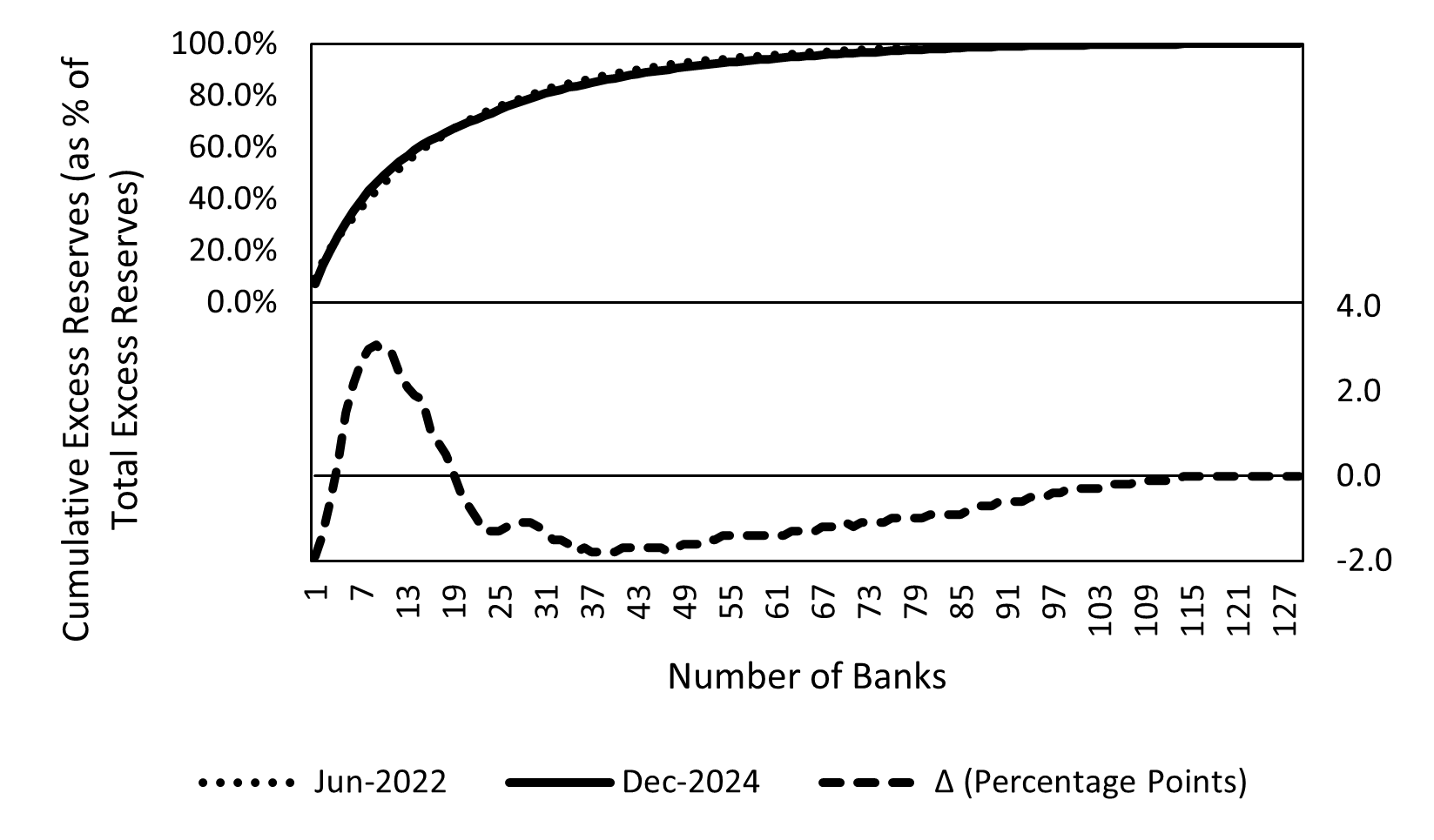

In the EA, excess reserves currently stand at around EUR 2.9 tn, a decline of almost 40% compared to the peak amount in 2022. The concentration of reserves in the banking system increased after the repayments of the TLTRO funds and the elimination of the related voluntary excess reserves since 2022. The excess reserves are concentrated in a limited number of mostly large lenders in the EA, whereas a majority of mostly small and medium-sized banks hold relatively small amounts of reserves in excess of their MRRs (Figure 72).

Source: ECB and EBA calculations

Figure 72b: EU/EEA banks’ cumulative excess reserves* and p.p. change between June 2022 and December 2024

[*] Cumulative excess reserves denote a measure of concentration of excess reserves

In a hypothetical scenario in which all excess reserves would be withdrawn from the system and the LCR outflow rates remained constant, banks would have to rely on alternative HQLA assets to meet their LCR requirements. Most banks already hold sufficient HQLAs even in the absence of excess reserves, but a few banks would breach their LCR requirements (the banks with negative numbers on the y-axis in Figure 73 bottom panel). These lenders would have to acquire primarily Level 1 HQLA components (such as government bonds or central bank reserves) rather than relying heavily on Level 2 assets to restore their 100% LCR minima. In the EA, a recent rise in volumes of term repo operations with maturities beyond 30 days suggests that banks may be seeking to improve their LCR ratios by exchanging Level 2 or non-HQLA assets for Level 1 assets in transactions that do not affect outflow rates[68].

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Aside from the prudential liquidity considerations, a reduction in central bank reserves also means that banks will have to manage their liquidity buffers more actively to ensure that they can meet their short-term financing needs. As reserves in the system will in the future be merely ‘ample’ and no longer ‘abundant’ as they are today, banks will have to increasingly cover their short-term liquidity needs by borrowing either from the central banks’ regular refinancing operations or from the secured money markets. To ensure a smooth transition to a state where central bank reserves are permanently lower, and to avoid volatility spikes in the overnight interest rates as banks’ activities in the money market increase, it is important for the banks, central banks and supervisors to anticipate when the aggregate liquidity conditions are likely to switch from ‘abundant’ to ‘ample’. There are signs that EU banks are already making such preparations, as seen in increased sovereign bond holdings and greater activity in the term repo markets beyond 30 days’ maturity. In those transactions, banks can pledge non-HQLA eligible collateral to obtain stable funding or transform it into HQLA assets, without triggering LCR outflows due to the longer maturities.

As EU banks will need to pay more attention to their liquidity requirements and liquidity management in the future, they may face new types of trade-offs between liquidity requirements and existing capital and resolution constraints. It is therefore important that banks and their supervisors monitor the situation carefully and plan for the new liquidity environment by proactively identifying pressure points that may arise from individual banks’ business models and balance sheet structures.

[68] On the rise of term repos volumes see the ECB blog post on the ‘The first year of the Eurosystem’s new operational framework’ from April 2025.