Liabilities: funding and liquidity

Table of contents / search

Table of contents

List of figures

Macroeconomic environment and market sentiment

Asset side

Liabilities: funding and liquidity

Capital and risk-weighted assets

Profitability

Operational risks and resilience

Special topic – CRE-related risks

Special topic –EU/EEA banks’ interconnections with NBFIs and private credit

Policy implications and measures

Annex I: Samples of banks

Search

Funding

Rising relevance of market-based funding in 2023

On the liability side of EU/EEA banks’ balance sheets, deposits remained the most important source of funding. A slowdown of customer deposit volume growth could already be observed in the first half of 2023, after a long period of strong deposit volume growth. In the second half of 2023, diverging trends between different types of deposits were observed. While the household deposit volume remained nearly unchanged, deposit volumes from NFCs and other customer deposits contracted in the second half of 2023. This comes in addition to a move from sight to term deposits.[1] In relative terms – when measured as a share of total liabilities – there have accordingly been no major changes for deposits. Household deposits had a share of 30.7% as of year-end (YE) 2023 (30.6% in 2022), NFC deposits 17.2% (17.1%) and other customer deposits 11.7% (11.1%).

The importance and volume of central bank funding continued to decrease in 2023. Other liabilities, which include deposits from central banks, decreased to a share of 14.4% in total liabilities at the end of 2023, down from 18.4% as of YE 2022. This decrease is not least driven by continued repayments of EA banks’ TLTRO funding. Data indicated that the main replacement for repaid TLTRO funding was debt securities issued, whose share in total liabilities rose from 17.4% to 19.7% by YE 2023. The rising relevance of market-based funding is similarly confirmed in market data, which shows that issuance volumes of secured and in particular senior unsecured debt increased in 2023 compared to previous years (Figure 17). However, market data suggests that issuance volumes of market-based funding decelerated in the first half of 2024, except for subordinated instruments (Figure 32).

Source: Dealogic, EBA calculations

*Based on publicly available market data which may not completely reflect all issuances of the different types of debt and capital instruments.

Positive market sentiment for bank funding so far in 2024

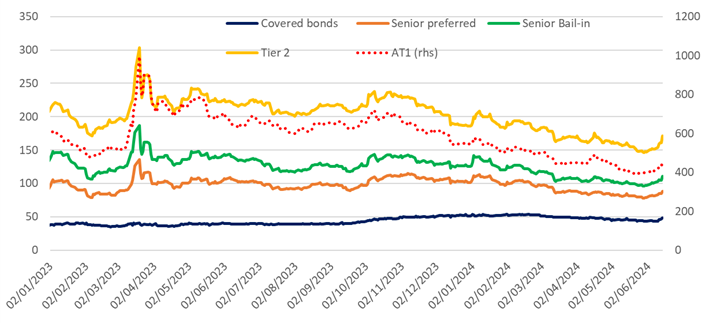

During the first months of 2024, strong fundamentals and high profitability with rising bank equity prices, underpinned by strong investor demand, supported decreasing spreads and had a positive impact on bank funding conditions. Despite some temporarily increasing spreads earlier this year, they steadily tightened for all main types of instruments. In relative terms, spread tightening was most pronounced for senior unsecured and Additional Tier 1 (AT1) instruments. They declined around 16% for the former and 17% for the latter in the year to date (YtD). Similar to AT1s, Tier 2 (T2) pricing also reached levels comparable to those before March 2023. In relative terms, T2 spreads have contracted by slightly more than 10% YtD in 2024. In contrast to unsecured instruments, spreads for covered bonds have contracted the least this year (slightly less than 10%). During the events in January and February 2024 related to New York Community Bancorp, Inc. (NYCB) and Aozora Bank Ltd, which were not least linked to their CRE exposures in the US, spreads of EU/EEA banks have hardly shown any impact. However, spreads showed rising divergence when the crisis materialised in March 2024, with spreads of particularly CRE-exposed banks facing a strong widening for all instruments across the capital stack. EU/EEA banks’ spreads across the board were negatively affected following the results of the European Parliament elections at the beginning of June, and the consequent snap election announcement in France.

Figure 18: Cash asset swap (ASW) spreads of banks’ EUR-denominated debt and capital instruments (in bps)

Source: IHS Markit*

*With regard to IHS Markit in this chart and any further references to it in this report and related products, neither Markit Group Limited (‘Markit’) nor its affiliates nor any third-party data provider make(s) any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of the data contained herewith nor as to the results to be obtained by recipients of the data. Neither Markit nor its affiliates nor any data provider shall in any way be liable to any recipient of the data for any inaccuracies, errors or omissions in the Markit data, regardless of cause, or for any damages (whether direct or indirect) resulting therefrom.

Banks’ focus in market based funding remained on unsecured instruments in the first half of this year (Figure 32). Issuances were placed by stronger as well as less well-known and commonly less active banks on primary markets. Issuance increased for T2 instruments. This was because banks were catching up on deferred T2 and AT1 instrument funding plans since 2023, after their issuance was near a standstill around the time of the bank market turmoil in March 2023 until about the middle of last year. The standstill happened last year when investor concerns about loss absorption of these instruments mounted. Very strong investor demand for higher-yielding instruments additionally supported T2 and AT1 issuance this year.

Issuance volume declined for senior preferred bonds and senior non-preferred (SNP) bonds as well as senior instruments issued from holding companies (HoldCo) in 2024 YtD compared to last year. However, 2024 YtD volumes are still above those seen in 2022 at this point in time of the year. Since SNP/HoldCo debt is mostly used to meet TLAC/MREL subordination requirements, the fact that banks had to comply with their MREL requirements by January 2024 might have resulted in a slowdown in issuance of these instruments this year compared to previous years (see on MREL-specific aspects Chapter 3.2). The covered bond issuances decreased as well during the first half 2024 compared to last year, but were above 2022 volumes. Factors that might explain covered bond issuances include a high volume of maturing covered bonds, as well as lower costs than for unsecured funding, especially at times of a temporarily more volatile market environment. Continued strong demand for covered bonds, including during periods of temporarily lower issuance volumes, provided opportunities for issuing banks to place covered bonds at comparatively low issuance premia.

MREL-specific aspects

In the EU/EEA, banks with a resolution strategy other than liquidation represent about 80% of total banking sector assets. Resolution strategies other than liquidation entail an MREL above minimum capital requirements, requiring banks to build loss-absorbing capacity, which means respective banks have to issue eligible instruments. Requirements to build loss-absorbing capacity have been an important driver for increased issuance volumes of in particular SNP/HoldCo instruments in recent years (see Chapter 3.1 on primary market developments, incl. continuously increasing SNP/HoldCo issuance volumes in recent years).

For the most part, banks had to meet their requirement by 1 January 2024. And as per the EBA’s latest MREL Dashboard as of 31 December 2023, all reporting banks are in compliance with the requirement set by their authority.[2] Still, 23 banks report a shortfall totalling EUR 8.0bn, or 0.1% of total risk-weighted assets (RWAs) in the sample and 1.6% of RWAs of banks in shortfall, as under certain conditions institutions may be granted a longer transition period.[3] In terms of stock, on average, MREL-eligible resources including own funds reached 33.1% of RWAs for global systemically important institutions (G-SIIs), 37.1% of RWAs for Top Tier (TT) and fished banks, and 27.2% of RWAs for other banks, of which 27.8%, 28.7%, 21.2% of RWAs are subordinated, respectively.[4]

On top of any outstanding shortfall, banks in the sample reported EUR 207bn of MREL instruments which become ineligible at the latest at the end of 2023 for falling below the one-year remaining maturity criterion (up 25% from last year’s publication but not on a comparable sample), i.e. this is outstanding MREL funding that banks need to refinance during the course of this year to keep their MREL levels (ceteris paribus).[5] Overall, this represents 18.1% of the total MREL resources other than own funds (Figure 19). These figures show that, although the vast majority of reporting banks already met their post-transition period MREL requirements by the end of 2023, issuance needs of MREL-eligible instruments continue to be significant, when taking the maturity criterion for eligibility into account.

Source: Reporting on MREL and TLAC

Out of this, EUR 62bn relates to G-SIIs (15.1% of their total MREL resources other than own funds), EUR 126.2bn to Top Tier and fished banks (20% of their total other than own funds) and EUR 20.4bn to other banks (18.9% of their total other than own funds). While those refinancing needs – assuming that banks indeed aim to refinance them as such – of over EUR 200bn are considerable, banks presumably reflected them in their funding plans. Compared to EU/EEA banks’ issuance volumes last year they should be in a position to again place comparable volumes of instruments this year as well, assuming no major market deterioration (see Chapter 3.1. on 2023 and previous years’ issuance volumes as well as primary market activity during the first months of 2024, and Chapter 3.4. on funding plans).

Asset encumbrance

The asset encumbrance ratio (i.e. the ratio of encumbrance of assets and collateral received to total assets and collateral received that can be encumbered) continues its decreasing trend that had started at the end of 2021. At that time it had reached more than 29%, and settled somewhat below 25%. On a YoY basis, the ratio decreased by more than 1 p.p. from 25.8% in December 2022 to 24.7% in December 2023. During the year, the decrease was mostly driven by two quarters of decrease in Q2 and Q4, which is not least supported by TLTRO repayments. Q1 and Q3 are marked by increases, with Q1 reaching the yearly peak of 26.5% (Figure 20).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Significant divergence between countries continues to be observed. Denmark remains the country in which banks report the most encumbered assets, which is mostly attributable to the large issuance volume of covered bonds for funding purposes. Conversely, many countries have very little asset encumbrance, such as Romania, Latvia, Lithuania and Croatia, where the average asset encumbrance ratio is below 2%. Czechia and Greece display the largest variation YoY, in a positive and negative direction by around 7 p.p. each. In the case of Czechia, the increase in the ratio is due to higher encumbrance of bonds issued by the general government.[6] This comes in parallel to a significantly rising share of deposits, which include repurchase agreements. The latter could explain the rising usage of sovereign bonds and accordingly increasing asset encumbrance ratio. In the case of Greece the decline in the asset encumbrance ratio is due to a decline in encumbered debt securities and loans and advances. The decline in the ratio might be explained by the TLTRO repayments during the course of the year. The EU’s/EEA’s largest jurisdictions, such as Germany (31.1%) and France (27.5%) continue to have a higher than EU/EEA-average asset encumbrance ratio (Figure 21).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Assets and collateral that are most encumbered are almost equally debt securities (45.5%) and loans and advances (43.0%). However, the long-term trend points to a decreasing share of encumbrance stemming from loans and advances and larger encumbrance from debt securities. This might be explained by the fact of declining central bank funding, such as TLTRO, for which certain loans are eligible collateral – in contrast to more market-based funding or other reasons for encumbrance, for which counterparties require debt securities as collateral (Figure 22).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

In the EU/EEA on average, a large part of banks’ assets is not encumbered and this share has increased over the past year from 79.6% to 81.9%, of which 15.6% were eligible for central bank funding as of December 2022 and 16.6% as of December 2023. This means that banks have increased the availability of assets that they can use for different means of funding, for instance. This can offer them important room for gaining new means of funding in times of stress when bond issuance might be negatively affected or deposits might decline. However, there is wide dispersion among countries in respect of unencumbered assets, and in particular of the share of unencumbered assets that are at the same time eligible for central bank funding. The share of the latter is for instance rather lower in some northern as well as some central and eastern European countries, whereas it tends to be in higher southern European countries (Figure 23).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

However, it is important to have in mind that for those purposes the fair value of these assets to be encumbered normally needs to be considered, i.e. it is the fair value – normally after additional haircuts – which then provides the room for gaining funding with available collateral. Data shown above is based on carrying amounts of respective assets and collateral. For this reason it is worth checking the difference between the carrying amount and fair value. Such analysis shows that, despite the rate rise of the past two years, the fair value of debt securities of which those eligible for central banks is largely unaffected. Over the past year, the unrealised losses on non-encumbered debt securities is not material, standing below 3%. A key reason might be that a certain share of the respective assets is already recognised at fair value through profit and loss (FVtPL) or fair value through other comprehensive income (FVtOCI) (Figure 24).[7]

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Funding plans

Forecasted changes in banks’ funding mix, with a rising share of deposit and bond issuances

Tightening monetary policy and the expiry of extraordinary central bank support measures led to a gradual substitution of central bank funding by market-based funding in the last two years. This trend is expected to continue in 2024 with banks forecasting deposits from central banks to drop significantly. By the end of 2024, central bank deposits are expected to represent 1.1% of banks’ total funding (down from 2.3% in 2023 and 5.6% in 2022). To compensate for declining central bank funding, banks intend to rely more on market-based funding and client deposits (Figure 25). The share of total debt securities issued over total funding is set to increase from 22.7% in 2023 to 23.5% in 2024. Client deposits are expected to represent 54.1% of total funding by the end of 2024 (53.6% in 2023). In 2025 and 2026, the withdrawal of central bank support measures will no longer have a significant impact on banks’ funding composition plans. The focus on client deposits is set to continue and banks are targeting a share of 54.9% of total funding by the end of the forecast period. Total debt securities are expected to represent 23.2% of total funding by 2026.[8]

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data (funding plan data)

Declining relevance of public sector funding

As of December 2023, banks’ total public sector funding in the EU/EEA amounted to EUR 503bn. Among the different types of programmes, long-term repo funding programmes – which include the ECB’s TLTRO programme – represented the biggest share with about 40% of the total public sector funding. According to banks’ plans, both the volume and composition of public sector funding are going to change substantially in 2024, with repos of more than one year almost completely disappearing due to the TLTRO funds reaching maturity (Figure 26).[9] Repos of less than one year, which cover central bank funding instruments like common LTRO and Main Refinancing Operations (MRO), as well as credit supply incentive schemes are also forecasted to decline. In contrast to long-term repos, however, these public funding sources will play a diminished but still existing role going forward. By the end of the forecast period in 2026, the public sector funding volume is expected to decline to EUR 182bn, less than 1% of banks’ total funding. Credit supply incentive schemes are set to become the dominant public funding support from 2024 onwards, reaching 80% of total public funding by 2026.

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data (funding plan data)

Banks are focusing on other liability classes to make up for the loss of central bank funding. The fastest growing liability class in 2024 is set to be debt securities. Within that class, long-term unsecured instruments are expected to increase by 4.9%, followed by long-term secured instruments at 4.6%. Banks also plan for an increase in short-term debt securities of 3.9%. Deposits, on the other hand, are forecasted to grow at a slower pace in 2024. Deposits from households, the biggest liability segment, are set to grow by 2.2% and deposits from NFCs are expected to grow by 1.4% in 2024 (Figure 27). Furthermore, banks this year plan for an increase in equity instruments of 4.6%.

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data (funding plan data)

Looking into 2025 and 2026, banks expect equity instruments to grow the most (4.9% in 2025 and 5.2% in 2026). Expectations for deposits from households and from NFCs are more optimistic compared to 2024 and banks plan an annual increase of 3.2% to 3.3% for both deposit segments in 2025 and 2026. After a strong increase in the previous years, short-term debt securities are expected to decrease by -3.9% in 2025 and slightly increase by 0.9% in 2026. Long-term secured and unsecured debt securities are expected to increase in 2025 by 4.1% and 2.3% respectively, with slightly lower growth rates in 2026 (3.9% and 1.2%).

Trends in market-based funding: rising issuance volumes

Over the three-year forecast period, EU/EEA banks plan to increase total long-term funding by 10%, reaching a total outstanding volume of EUR 4.6tn in 2026 (EUR 4.1tn in 2023). For 2024, banks in all countries plan for a significant net issuance volume, with banks in Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden reporting the highest planned net issuance volume. High net issuances are probably not least due to the need to cover large amounts of maturing TLTRO funding. In 2025 and 2026, banks expect net issuance volume to be significantly lower. For most countries, banks still plan for positive net issuance volume. Banks in several countries expect a negative net issuance volume in either 2025 or 2026. In most cases this either follows or is followed by a year of positive net issuances (Figure 28).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data (funding plan data)

Zooming in on unsecured debt securities, the total outstanding volume is expected to increase by 8.6% over the forecast period, to EUR 2.70tn in 2026 compared to EUR 2.49tn in 2023. For each year of the forecast period, banks plan to issue more unsecured debt than will mature. Net issuance volume is highest in 2024, and particularly so for senior non-preferred and senior preferred debt (Figure 29).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data (funding plan data)

Banks plan to issue a significant volume of unsecured debt in each year of the forecast period. 2024 is expected to be the year with the highest issuance volume, reaching almost EUR 500bn. With banks planning to issue EUR 278bn of senior preferred, EUR 100bn of SNP and EUR 55bn of senior Holdco instruments, the total unsecured issuance volume in 2024 is set to be almost 20% higher than in 2023. The strong increase in issuance volume is particularly notable for AT1 instruments and T2 instruments. With a combined volume of EUR 62bn planned for the two capital instruments, the previous year’s volume would be surpassed by EUR 38bn, an increase of 158% compared to 2023. The rise in issuance volume of AT1 and Tier 2 instruments relates to rather low volumes in 2023 and 2022, with both years impacted by central bank rate hikes and events with a major impact on these debt classes (e.g. Credit Suisse, as also covered in the last edition of the EBA’s Risk Assessment Report).

Issuance volume of unsecured instruments is set to stay high in 2025, mainly driven by a high volume of maturing debt. Banks plan to issue EUR 262bn of senior preferred, EUR 107bn of SNP and EUR 62bn of senior Holdco instruments in 2025, resulting in a positive net issuance volume for each of the debt classes. For AT1 instruments, banks expect another year of strong issuance volume with EUR 18bn (vs EUR 11bn maturing). For Tier 2 instruments, the planned 2025 issuance volume of EUR 37bn is below the maturing volume of EUR 41bn. In 2026, banks’ forecasts point to another year of high issuance volume and positive net issuances for the two main debt classes, senior preferred and SNP instruments. For the other debt classes including AT1 and Tier 2 instruments, issuances are expected to fall below maturing volumes.

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data (funding plan data)

Banks plan to strongly increase secured funding issuances in 2024 and keep them at a high level in 2025 and 2026. Compared to 2023, the total issuance volume of long-term secured debt is expected to almost double to about EUR 348bn in 2024 (EUR 179bn in 2023). The issuance volume of covered bonds is expected to reach EUR 284bn in 2024, followed by EUR 303bn in 2025 and EUR 309bn in 2026. The strong increase in covered bond issuance in the forecast period is largely driven by a high volume of maturing covered bonds in this period. Yet the issuance volume of covered bonds is forecasted to substantially exceed the volume of maturing covered bonds in each year of the forecast period, representing a total net issuance volume of EUR 220bn for the forecast period. This indicates banks’ plans to replace maturing central bank funding with covered bonds and may reflect the fact that covered bonds can offer a cheaper source of funding than unsecured funding.

Banks also expect a very strong increase in issuances of asset-backed securities (ABS), to EUR 53bn in 2024, EUR 45bn in 2025 and EUR 42bn in 2026, from about EUR 12bn in 2023. Regulatory and policy initiatives to facilitate and promote securitisations could contribute to banks’ plans for strongly increased ABS issuance. Issuance volumes of other secured long-term debt are expected to stay close to the 2023 level of EUR 12bn throughout the forecast period.

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data (funding plan data)

Banks’ planned issuance volume for 2024 can be compared with actual bond issuances recorded in the first three months of 2024. While the coverage of banks and issuances differs for the two data sets, a comparison of trends in actual versus planned bond issuances can provide an indication on the feasibility of banks’ issuance plans. Primary market data shows that banks placed a high volume of bonds across all bond segments (see Figure 32 and Chapter 3.1 on primary market activity last year and in the first months of 2024). Despite their decline compared to last year, issuance volumes were still high in the first half of this year. If full-year 2024 plans are to be met, bond markets will need to show high activity levels for the remainder of the year. This is particularly true for covered bond markets, given the planned increase in issuance volume for 2024 (Figure 31). Planned high issuance volumes might become more difficult if financial markets show elevated levels of volatility as it was the case in June. It will also be important that banks use windows of opportunity for their issuances, to avoid bond placements in times of high prices, for instance.

Source: Dealogic

*Based on publicly available market data which may not completely reflect all issuances of the different types of debt and capital instruments.

Liquidity positions

Liquidity positions continued to be strong in 2023, and well above minimum requirements, with a LCR of 166% and an NSFR of 127% in 2023.[10] Funding plan data indicates that liquidity positions are expected to remain solid over the funding plan horizon. However, EU/EEA banks’ LCR is expected to decrease to 153% in 2024. Outstanding TLTRO amounts that EA banks took up from the ECB were at around EUR 400bn at the beginning of 2024 but need to be repaid by the end of this year. Since a declining LCR according to funding plans is mainly driven by declining liquidity buffers (high-quality liquid assets – HQLA), the LCR numerator, it can be expected that a declining LCR is not least driven by these TLTRO repayments, which are presumably at least in part served from cash held at central banks, for example.[11] The expected decrease in the NSFR in 2024 is mostly driven by higher net stable funding needs, presumably driven by higher growth in respective assets compared to the smaller rise in related liabilities. The NSFR is expected to increase again in 2025 and 2026, driven by a stronger increase in available stable funding (the numerator) – presumably explained by the bigger rise in deposits and bond issuances in those years again – than in the required stable funding (the denominator).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

[1] This was, for instance, also covered in the last edition of the EBA’s Risk Assessment Report from December 2023.

[2] Four banks report a technical shortfall, two of them already solved and no more in shortfall and two pending entry into force of CRR3. MREL dashboard Q4 2023

[3] The shortfall is calculated the same way as in the EBA’s MREL Dashboard, using weighted averages of the higher of the MREL requirements calibrated using (i) total risk exposure amount + combined buffer requirement and (ii) total exposure measure.

[4] Top Tier banks are non G-SIIs with total assets above EUR 100bn, and fished banks are non G-SII, non Top Tier banks selected by the relevant resolution authority as being likely to pose a systemic risk in the case of failure.

[5] There are other drivers for potential changes in MREL levels, such as a rise in assets or RWAs, changes due to new MREL decisions of resolution authorities, etc.

[6] According to the supervisory reporting instructions, general government includes central governments, state or regional governments, and local governments.

[7] See, for instance, data on sovereign exposures in the EBA’s Risk Dashboard, according to which around 35% of these exposures are measured at fair value (FVtPL, held for trading [HFT] and FVtOCI).

[8] As described in the Introduction, there are partially certain differences between reporting samples and entities as well as reporting requirements, such as in the level of consolidation. This is the reason why, for example, the funding composition data based on funding plan reporting in this chapter differs slightly from the data shown in Chapter 3.1, which is based on FINREP.

[9]It is also important to be aware of the potentially negative impact from the cessation and wind-down of the ECB’s different asset purchase programmes, which might affect market liquidity.

[10] Based on funding plan data which cannot be fully reconciled with EBA liquidity reporting data (see explanations in the Introduction).

[11] The repayment of TLTRO will also release previously encumbered assets. However, these are presumably only in part HQLA-eligible assets. According to an ECB article from 2021 on TLTRO III and bank lending conditions the encumbered non-HQLA collateral reached nearly 75% of banks’ TLTRO.