Special topic –EU/EEA banks’ interconnections with NBFIs and private credit

Table of contents / search

Table of contents

List of figures

Macroeconomic environment and market sentiment

Asset side

Liabilities: funding and liquidity

Capital and risk-weighted assets

Profitability

Operational risks and resilience

Special topic – CRE-related risks

Special topic –EU/EEA banks’ interconnections with NBFIs and private credit

Policy implications and measures

Annex I: Samples of banks

Search

Financial intermediation in the EU/EEA has traditionally been a business for banks. In the years after the global financial crisis, technological innovation, regulatory reform and the urge to bolster EU/EEA capital market activity have contributed to growth in financial intermediation outside the banking system, where parts of the activity may remain less regulated. Several types of interconnections can be identified between banks and NBFIs, with both benefits and risks arising from such linkages. In terms of volumes, non-bank intermediation in the EU/EEA remains moderate compared to some other major jurisdictions.[1] That notwithstanding, ongoing monitoring of the sector is necessary to identify emerging risks and vulnerabilities which, if crystallised, could propagate to the banking sector via both on and off-balance-sheet channels. Special attention should be paid to non-bank lending activity, a relatively novel area for non-banks which has seen particularly dynamic growth recently.

EU/EEA NBFIs are inexorably intertwined with banks and non-financial sectors

The landscape of the EU/EEA financial system is characterised by complexity and interconnectedness. Financial linkages serve to improve risk-sharing, which makes the financial system safer, less concentrated and more efficient. At the same time, cross-funding links also provide channels of contagion and propagation that could be activated in periods of stress. Identifying sources of systemic risk therefore requires detailed understanding of the financial flows in various instruments among the different sectors of the economy. Quarterly sectoral accounts (i.e. the ‘who-to-whom’ data from national accounts) and detailed EBA supervisory reporting data provide useful insights into the interconnectedness of the EU/EEA financial system, including links of NBFIs to both banks and the non-financial sectors.

The sectoral accounts data, such as the System of National Accounts, provides a coherent, consistent and integrated set of macroeconomic accounts for an economy using internationally agreed definitions and accounting rules. Who-to-whom data tracks the flows between different sectors of an economy (i.e. here the EA), and covers the balance sheets of ten sectors on an unconsolidated basis, including the real economy (i.e. households and NFCs), the public sector (i.e. general government and central banks) and the financial sector (i.e. monetary financial institutions (MFIs), insurance corporations (ICs), pension funds, non-money market fund (MMF) investment funds (IFs) and other financial institutions(OFIs)). An additional sector is the rest of the world, which includes all countries outside the EA.

The EA banking sector provides financial intermediation services to the other financial and non-financial sectors through a variety of instruments, including loans, deposits, securities and derivatives. Based on sectoral accounts data, banks are mostly linked to non-banks via asset and liability exposures in loans and deposits, whereas NBFIs are major holders of bank-issued debt securities. The links of the banking sector to the NBFIs are somewhat more pronounced on the banks’ liabilities side (i.e. funding links) (Figure 65).

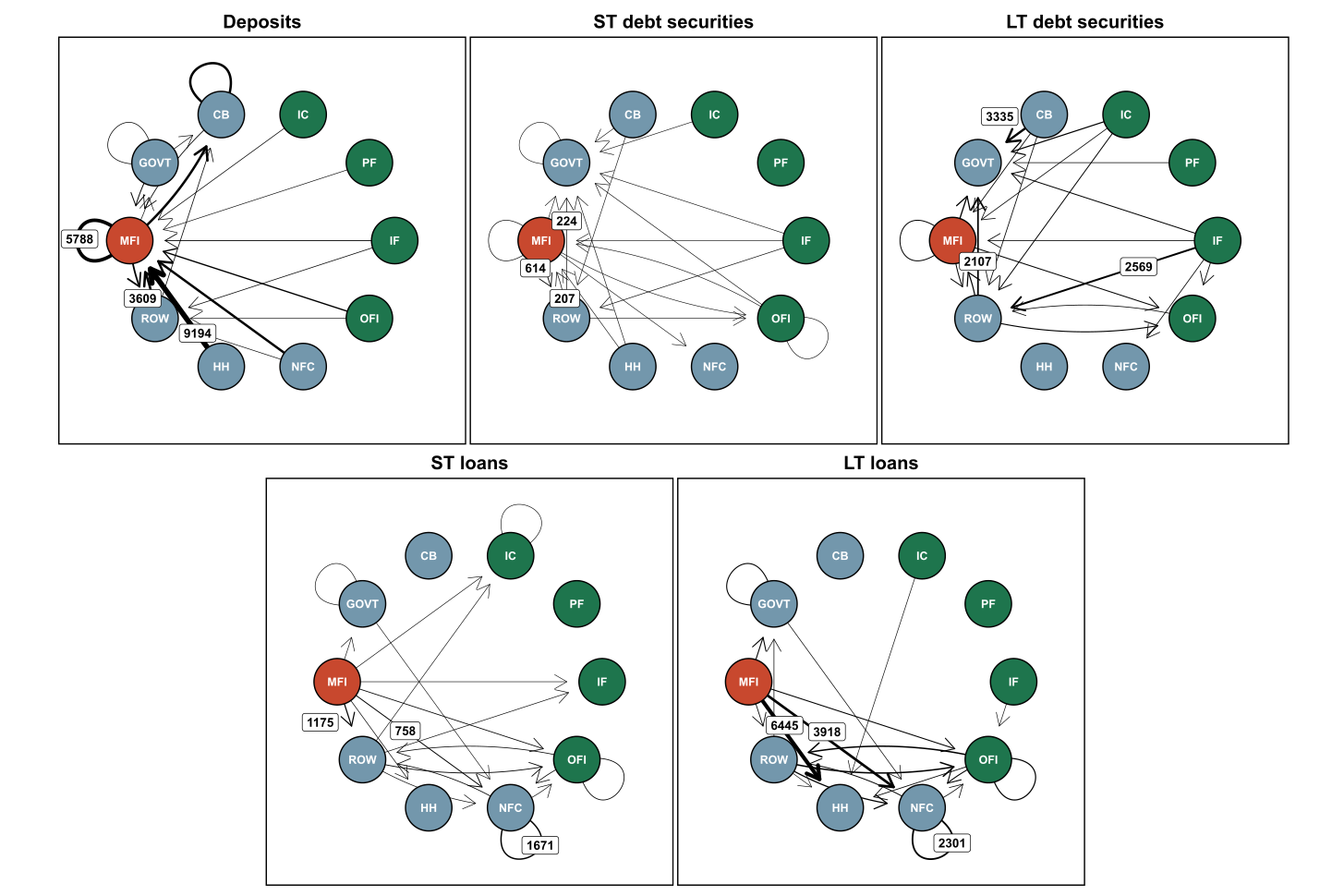

Figure 65: Network of the EA financial system comprising links between the banking sector and other sectors of the economy, December 2023 (the values of the three largest exposures are shown next to the respective arrow in each of the charts) (EUR bn)

Source: ECB/Eurostat and EBA calculations. Arrows run from assets to liabilities. Data reflects EA 20 exposures. Only the 20 (3) largest links are shown (highlighted) in each chart, respectively. Charts are represented on a common scale, with thicker arrows indicating higher exposures. MFI: Monetary financial institutions (excl. central bank); GOVT: General government; CB: Central bank; IC: Insurance corporations; PF: Pension funds; IF: Non-MMF investment funds; OFI: Other financial institutions; HH: Households incl. non-profit institutions serving households; ROW: Rest of the world.

As of December 2023, NBFI holdings account for more than a quarter of total bank-issued debt in the EA. Among the NBFI sectors, the OFIs sector and the IFs sector each hold some 12% of all bank-issued short and long-term debt securities. However, banks also have important exposures to NBFIs on the asset side, as they provide short-term loans (such as [reverse] repos) to NBFIs. Of all short-term loans originated by EA banks more than one-fifth are extended to NBFIs.[2] From a holistic perspective, the OFI sector is most extensively linked to MFIs, especially in terms of deposits, short-term debt securities and short-term loans, while IFs and ICs are mainly interconnected through the holding of long-term debt securities issued by MFIs; the total assets of the OFI sector are almost 1.4 and 2.6 times larger than those of IFs and ICs, respectively.

Bank-level information shows that EU/EEA banks’ NBFI linkages are concentrated on specific instruments and business models

Supervisory data at individual institution level provides further details about the links between banks and NBFIs.[3] EU/EEA banks’ exposures to NBFIs amount to 9.2% of consolidated bank assets as of December 2023 (Figure 66). Large banks are generally more connected to the non-bank sector, with exposures amounting to 9.7% of total consolidated assets, followed by medium-sized banks (5.4% of total assets), and small banks (5.1% of total assets).[4] Exposures to NBFIs show an increasing trend since the end of the pandemic. Among individual asset categories, OTC derivatives have seen the highest growth rates with rather substantial fluctuations in volumes. However, those changes in respective exposures are not necessarily driven by rising OTC derivatives business between banks and NBFIs, but also, for instance, valuation effects. Exposures in trading loans also showed major volatility between 2021 and 2023 (which might equally be explained by valuation effects) whereas other loans (i.e. those not classified as trading) rose in the past and then showed a more stable trend (Figure 67). Going forward, banks indicate that they plan to increase lending to other financial institutions by ca. 2% annually in 2024-2026 (see on EU/EEA banks’ asset growth plans Chapter 2.2, including Figure 9 with a breakdown of banks’ forecasts).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

A closer look at the distribution of banks’ non-bank exposures reveals that asset linkages are concentrated in few institutions with specialised business models: twenty banks which represent 38% of the total assets of the sample cover 62% of the exposure to the NBFI sector. Although the amount of the exposures towards the non-bank sector is concentrated in these few banks, their individual exposures relative to their balance sheet sizes are not amongst the biggest of the sample. Banks with outsized exposures to NBFIs are medium-sized institutions with specialised business models, such as investment banking, market making and (reverse) repo lending, whilst the largest banks report exposures that are closer to the EU/EEA average (Figure 68).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

On the liability side, NBFI funding for EU/EEA banks – excluding wholesale market-based funding, such as through debt securities issued –amounts to 10.3% of total assets. For large banks, these links are mostly repo funding, whereas for small and medium-sized banks they are mostly through term deposits. Unlike the asset exposures, EU/EEA banks’ respective liabilities to NBFIs have remained broadly stable on aggregate, as the drop in current account deposits has been offset by a moderate upward trend in other liability items (Figure 66 and Figure 67). In terms of wholesale market-based funding, NBFIs are also amongst EU/EEA banks’ main funding counterparties.[5] Based on the reporting on main funding counterparties, repurchase agreements represent 67.7% of the total funding received from NBFIs classified as main funding counterparties, followed by unsecured wholesale funding (20.8%) and intragroup funding (8.6%) (Figure 69).[6]

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

* The group of ‘other’ funding counterparties includes those items for which banks did not report any specific counterparty classification.

EU/EEA banks also have important links to NBFIs via off-balance-sheet exposures. As of December 2023, undrawn loan commitments, financial guarantees and other commitments extended to NBFIs amounted to 6.4% of all off-balance-sheet items (Figure 70). The share of off-balance-sheet exposures to NBFIs is higher and less diversified in type for smaller banks compared to medium-sized and larger banks. At the same time, the NBFI sector is an important provider of financial guarantees to EU/EEA banks. The share of undrawn loan commitments, financial guarantees and other commitments received from NBFIs amounted to 9.0% of EU/EEA banks’ total off-balance-sheet items as of December 2023 (Figure 70). Large banks are more frequent users of financial guarantees and other off-balance-sheet commitments from non-banks (9.5% of total off-balance-sheet items), while medium-sized and smaller banks receive only a small share of their total off-balance-sheet items from NBFIs (1.9% and 2.1%, respectively).

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Source: EBA supervisory reporting data

Off-balance-sheet exposures could become a channel of contagion from non-banks to banks if credit lines were drawn simultaneously by several large NBFI counterparties. Since NBFIs lack the access to public safety nets, such as public deposit guarantee schemes and central bank liquidity facilities, they may have an incentive to access support indirectly via off-balance-sheet links to regulated credit institutions which are covered by such emergency facilities.

Direct lending by NBFIs (private credit) creates novel challenges for EU/EEA banks

The empirical interconnections illustrated above identified loans as one of the growing areas of non-bank finance. Such direct lending by non-banks to households and firms is also loosely called ‘private credit’. In the EU, the volumes of direct non-bank lending remain relatively modest in comparison with some other major jurisdictions, notably the US, but the growth rates have been rapidly accelerating in several Member States.[7]

The growth in private credit in the EU/EEA has coincided with several ongoing trends. From the EU/EEA banking sector perspective, the Basel III regulatory reform agreed at the global level in 2017 and currently being implemented by Member States may have created incentives for banks to adjust balance sheets to comply with the new requirements.[8] For individual banks, the adjustment process may have involved refocusing of activities and/or reducing certain more capital-intensive practices. From the borrowers’ perspective, the pandemic, the sharp increase in interest rates to offset the global inflation shock, and the subsequent tightening of bank lending standards created challenges especially for firms and households with weaker balance sheets. Many borrowers also faced sudden refinancing needs due to specific business model issues (e.g. CRE) or inability to access the public equity markets as planned (e.g. private-equity-owned portfolio companies). The higher interest rate environment also adversely affected the cost of debt financing for funds active in the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and buyout markets, pushing asset managers and private equity funds to seek alternative ways of deploying capital. Finally, the arrival of new players in the lending market, including FinTech companies, has added to the supply of loanable funds competing for profitable projects.

This combination of developments has contributed to an environment where (i) banks were looking to reduce their activities in certain, more capital-intensive businesses, (ii) many borrowers with higher risk profiles were facing steeply higher financing costs and (iii) new alternative credit providers were looking to enter the lending market. But the spectrum of borrowers and lenders has gradually widened and now covers lending by specialised funds and firms to areas such as SMEs, infrastructure projects, real estate and consumer credit.

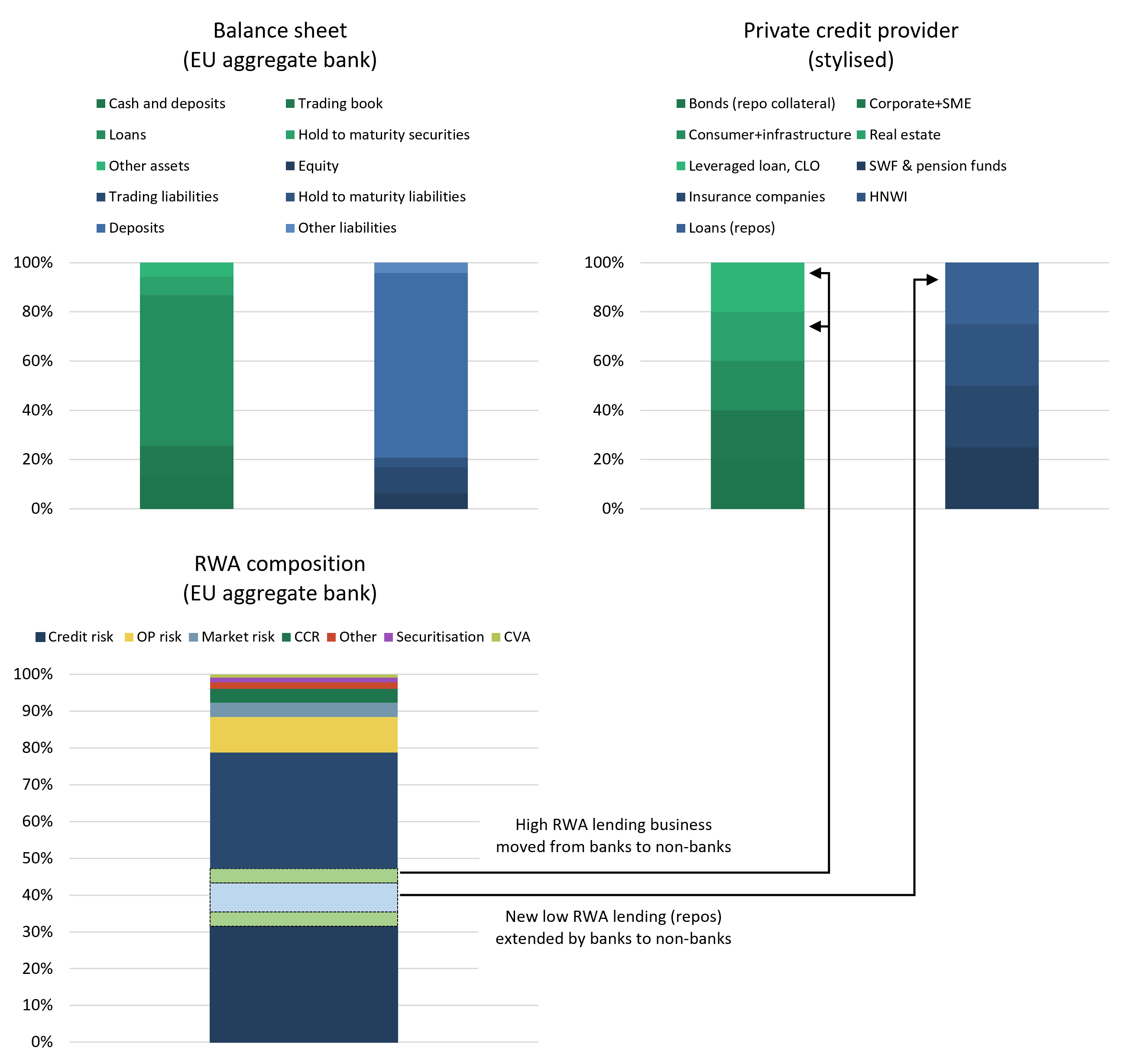

The links between the banks and the non-bank lenders can be illustrated by a simplified balance sheet of the EU/EEA aggregate bank, using the EBA Transparency Exercise data, as well as the balance sheet of a stylised non-bank lender.[9] The lending on the private credit providers’ asset side is financed by funds raised from investors — including insurance firms, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and family offices — which themselves seek to match long-term liabilities with long-term assets, such as loans to non-financial sectors. Importantly, the liabilities of the private credit providers also include leverage (debt financing) to enhance the returns to their investors. Although such leverage is typically only a fraction of the proportion incurred by banks, for non-banks the leverage is mostly created by short-term borrowing from the repo market instead of more stable deposit funding in the case of banks. The latter also benefit from partial protection of deposit guarantee schemes.

Figure 71: Illustrative examples of a bank’s and a private credit provider’s business and how they are linked*

Source: EBA, using, for instance, anecdotal evidence, EBA Transparency Exercise data and further market research/analysis**

* A potential additional link is that the final borrower from the bank and the private credit provider might be the same in which case financial distress experienced by the borrower would affect all lenders depending on the seniority of their exposures.

** CLO – collateralised loan obligation, SWF – sovereign wealth fund, HNWI – high-net-worth individual.

Banks may achieve capital relief by deprioritising activity in high-RWA businesses (or by selling loan portfolios outright) and in this way either shrink their balance sheets or replace the assets with lower-risk-weight exposures.[10] For a bank, one possibility to compensate for the high-risk-weight activities is to increase short-term lending to non-bank counterparties which, depending on their type, may qualify either as ‘institutions’ (like banks, if they are classified as investment firms) or ‘other corporates’. In both cases the risk weight assigned to the new exposures is likely to be lower than the original exposures.[11] To complete the circle of exposures, non-banks — which above were shown to be significant holders of bank-issued debt securities — could then post banks’ bonds as collateral in the secured borrowing (repo) transactions with banks, thus creating both on- and off-balance-sheet links between the two types of lenders. Such two-way links in bank-issued debt securities would give rise to a funding liquidity risk for both parties of the transaction.

Banks may also decide to set up explicit partnerships with non-bank lenders and in that way remain involved in lending activities that they prefer not to grow on their own balance sheets. Such partnerships can take the form of joint ventures or direct equity ownerships.[12] Partnerships are beneficial to both banks and non-banks as they combine the banks’ strengths in infrastructure, experience, risk management and regulatory issues with non-bank partners’ strengths in customer acquisition, product development and user experience. However, they also establish channels through which shocks can be transmitted to banks in ways which may not be fully foreseen by the banks’ stakeholders and counterparties.

From the broader financial stability perspective, it should be emphasised that the arrival of new players in the lending market is a welcome development. For the borrowers, increased competition should improve access to finance and reduce financing costs. For the wider economy, better risk sharing and more projects getting financed means more investment at the macro level, which is particularly relevant in areas like green transition, ageing societies, economic security and other current and future policy objectives.

At the same time, there are also risks. First, lenders which are not regulated as credit institutions might not apply lending standards that are as prudent as those of their competitors in the banking sector. On the one hand, credit may be extended to less creditworthy borrowers, creating higher default risks in a downturn. On the other hand, creditworthy borrowers may be charged excessively high fees and interest rates, leading to lower investment and slower economic growth. In this vein, one key area to be monitored is whether at the aggregate level the potential shift in lending from banks to non-banks contributes to increased or reduced lending to the non-financial sectors. Second, if non-banks were to capture meaningful market share in some lending segments, such as consumer credit or SME lending, in the event of economic downturn or market stress several of them could withdraw simultaneously, leaving borrowers stranded and creating unforeseen financial stability risks. Third, questions can be asked about the resilience of non-banks to cyber-attacks, and their ability to protect sensitive customer data and to comply with anti-money laundering and customer identification rules. Fourth, the shareholders of some non-bank lenders may follow more short-term incentives than their peers in the banking industry. The ability to provision for expected losses and to withstand unexpected losses may be weaker than that of banks which have the experience of managing risks throughout the full credit cycle. Finally, both on and off-balance-sheet linkages may allow non-banks to indirectly access the public safety nets through banks, such as central bank liquidity facilities, that at present are exclusively available for regulated credit institutions. It is important that the clients of non-bank lenders are fully aware that these players — although typically less leveraged than banks and often funded by long-term investors in closed-end structures — are not protected by the same emergency facilities as credit institutions. All in all, close monitoring of these developments and cooperation between regulators, supervisors and central banks are necessary to ensure that the risks in private credit are fully identified and appropriately dealt with.

Finally, it is important to note that in the EU most non-bank lenders are regulated even when they are not classified as credit institutions. Insurance companies, which are regulated under Solvency II, have taken on some lending activities. Investment firms are covered by the new Investment Firms Directive (IFR/IFD), with the largest ones being classified as credit institutions. And alternative investment firms have their own standards and rules, including recently updated loan origination guidelines. But some of the new players in the market, including FinTechs, may not be regulated as financial intermediaries. Going forward — and keeping in mind proportionality and the specificities of the non-bank sector that distinguish it from the banks — the usual catchphrase of ‘same risks, same regulation’ serves as a useful guidepost. This is to guarantee that a level playing field between banks and non-banks is preserved, that consumer protection and access to finance at a fair price are respected, and that financial stability risks are identified and properly addressed.

[1] Amid lack of evidence for certain parts of the following analysis, this chapter is partially also based on schematic presentation. The growth and relevance of the sector is reflected by the fact that several new EU regulatory initiatives, including the (Alternative) Investment Firms Directive, Payment Services Directive and Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation, have been introduced to provide a sound regulatory basis for specific areas of non-bank finance.

[2] There are also significant exposures of the EU/EEA IF sector to the rest of the world (ROW) sector, suggesting that investment funds provide an important vehicle for EU/EEA residents to access debt and equity markets outside of the EU/EEA internal market.

[3] To provide further details on the interconnections between EU/EEA banks and NBFIs, bank-level consolidated data from FINREP is used. This data provides a more granular breakdown in terms of financial instruments, but treats the NBFIs as one aggregate sector, including insurance, pension funds, other financials and investment firms.

[4] The asset exposures are concentrated in loans classified in non-trading portfolios (3% of total assets), followed by OTC derivative assets (1.9% of total assets), loans for trading activities (1.6% of total assets), reverse repos (1.3% of total assets), debt securities (1.2% of total assets) and equity exposures (0.4% of total assets).

[5] The main funding counterparties cover the top 10 counterparties where the funding obtained from each counterparty or group of connected clients exceeds a threshold of 1% of total liabilities. The funding provided by the main funding counterparties represents 6.1% of consolidated bank assets.

[6] Unsecured wholesale funding includes debt securities issued, but also loans and deposits received.

[7]Chapter 2 of the spring 2024 IMF Global Financial Stability Report focused on the rise and risk of private credit from the global perspective. The ECB spring 2024 Financial Stability Review included analysis of non-banks as funding providers to EA banks. The focus here is on the interactions specifically between banks and non-bank lenders, including not only funding links but also ownership, lending, and off-balance-sheet interconnections. Since non-bank lending/private credit is a new area of activity and carried out by various types of NBFIs, precise statistical information about its size is still difficult to obtain. The ECB estimates that as of the third quarter of 2023, assets under management of euro area private market funds (including private equity and private credit) stood at EUR 960bn, or 6% of the euro area investment fund sector’s total assets, which is substantially smaller than in the US. The compounded annual growth rate of the private credit segment is estimated at 14% (see e.g. ECB Financial Stability Review from May 2024 and ECB IVF statistics).

[8] The comprehensive EBA impact assessment published in 2019 on the impact of Basel III quantified the estimated increases in bank capital requirements. Using data as of June 2018, the estimated increase in Tier 1 minimum required capital amounted to 24.4%, on average, for all banks in the sample. The estimated Tier 1 capital shortfall amounted to EUR 127.7bn. The 2023 regular EBA Basel Monitoring Report, using data as of December 2022, estimated that the adjustment had been practically completed.

[10] If the lending activity deprioritised by the banks is taken up by private credit providers, the outcome may resemble a transfer of credit risk out of the banking sector without explicit securitisation arrangements.

[11] In practice, the short-term lending would often take the form of reverse repurchase agreements whereby the banks would extend short-term loans to borrowers who post securities as collateral. For example, a bank could reduce lending to commercial real estate, project financing, or SMEs, with typical risk weights ranging from 85-130%, and replace it with repo lending to an investment firm with a risk weight of 5-10%, or a fund classified as “other corporate” with risk weights ranging between 10-66%. The banks’ risk-based capital ratio would then improve whereas its total assets or leverage ratio may remain unchanged.

[12] In the EU, many large asset managers already tend to be parts of banking groups. This is different to the US and the UK, where large asset management companies are mostly independent and sometimes also major shareholders of banks.